September 30, 2005

Put Bill Bennett in a statistics class

Bill Bennett has completely stepped in it, and there's just nothing to say to mitigate it:

On the Wednesday edition of his radio show, "Bill Bennett's Morning in America," syndicated by Salem Radio Network, a caller raised the theory that Social Security is in danger of becoming insolvent because legalized abortion has reduced the number of tax-paying citizens. Bennett said economic arguments should never be employed in discussions of moral issues.If it were your sole purpose to reduce crime, Bennett said, "You could abort every black baby in this country, and your crime rate would go down.

"That would be an impossible, ridiculous and morally reprehensible thing to do, but your crime rate would go down," he added.

It's difficult to know where to begin. I really don't think Bennett is racist, in a "I don't like black people and wish they were all aborted" way. And he's referring to a statistical fact: A higher percentage of blacks are arrested and incarcerated for crime in this country compared to whites or other races. By higher percentage, I mean more in relation to their total population:

The paper, appearing in the most recent American Sociological Review (published by the American Sociological Association), estimates that 20 percent of all black men born from 1965 through 1969 had served time in prison by the time they reached their early 30s. By comparison, less than 3 percent of white males born in the same time period had been in prison.

Whites are arrested and incarcerated in higher numbers, blacks are arrested and incarcerated at higher rates. So removing an entire generation of black men would drop the crime rate disproportionately as compared to removing an entire generation of white men, although removing the white men would probably drop it a lot more in terms of actual numbers. It was a very poor choice of example for Bennett to use, because understanding his point requires a decent understanding of statistics, specifically crime correlations, and his audience just didn't have that, nor should he have expected them to.

From reading the article on the controversy, I think I get his point: The caller was saying that abortion had removed people paying into Social Security so that's why it's in trouble. Bennett was saying, yes, but an economic calculus is not the reason to decide for or against abortion, because the segment of society more likely to get abortions is the same segment of society that is disproportionately arrested and incarcerated for crime. So if you use an economic calculus as your standard, you would be for abortion as a means to reduce crime. The cost-benefit analysis from an economic standpoint is actually in favor of abortion if you consider only the effects on crime and social programs - because the segment of society that uses social programs the most heavily is also the segment of society most likely to get abortions. However, such a cost-benefit analysis is truly morally reprehensible, because people are not spreadsheets and the value of their lives should not be assessed based on whether they will give more to society economically than they take away. Some give a lot economically, some give in other ways, and all of those ways are valuable and important. And, let's face it, some who gave hugely in economic ways later took much more than they gave - Enron, anyone?

Actually, I think that was just Bennett's point: Cost-benefit analysis using just economic considerations is wrong. His example was... stupid. I don't think the FCC should kick him off the air, but I do think someone should put him on time delay just for his own benefit.

A note on crime correlation: We've just been going over this in my Intro to CJ class, and I think it's something everyone should have a good grasp of. In statistics, you rarely can say something causes something else, especially in the social sciences. You more often can say that some condition is predictive of something. Studies have found that people who are poor are more likely to commit street crimes than people who are not poor; people who are black are more likely to commit street crimes than people who are white. Does that mean being poor or black also means you're a criminal-in-waiting? Not at all. Poor whites are also more likely to commit crime than more economically secure whites. The statistical finding that blacks are more likely to commit street crime is likely an artifact of other conditions found disproportionately among the black population in the US - poverty and lack of education, for example. So a white person and a black person with the same socio-economic level and education are equally likely to commit crime.

It is true that black men, especially, are incarcerated at a much higher rate than white men. But there again, it has nothing to do with race, and more to do with other factors. For example, we in this country focus our law enforcement attention more intensely on street crimes - murder, robbery, burglary, drugs, for example - than we do on white collar crimes - embezzling, stock frauds, etc. You can only do crimes you have opportunity to do, and the poor don't have the opportunity to do much embezzling and stock frauds - they do street crimes. So the kind of crimes poor black men engage in are disproportionately targeted in comparison to the whole range of crimes likely committed. Also, once you identify a certain place - say, a public housing project - as a likely site for criminal activity, you're going to put more enforcement power there. Four eyes will always see more crime than two eyes, so an increase in enforcement means an increase in arrests that may give the appearance of more crime, which in actual fact it is just an increased detection of a possibly-stable level of crime.

Crime is a very tangled problem, but I've never seen any indication anywhere that race has a causal relationship to it. It just doesn't. A man as smart as Bill Bennett knows that. So to use the example he did was thoughtless and stupid because of the impression it creates, although probably his example was at its core accurate, for reasons I've outlined above. Someone get the guy an editor.

UPDATE: La Shawn Barber hammers home the obvious: There's a difference between alluding to a statistical fact and wishing that it would come to pass.

September 27, 2005

Amen to WaPo

It's not often that I agree with the Washington Post on something with political implications, but they nail it precisely with this hammering of Louisiana demands for reconstruction.

I don't mind helping out people who have had their everyday life ripped from them by nature. I'd much rather do that than fund, say, Planned Parenthood. But I absolutely do not agree with allowing them to rebuild in flood plains, with subsidized flood insurance so they can live there, to rebuilding communities that will be destroyed again and again just because they were once built where they shouldn't have been. It's like subsidizing people to build cantilevered homes out over a California slope that will, inevitably, succumb to earthquake or mudslide in the not too distant future. History and wonderful scenery are important things, but I shouldn't have to pay higher taxes so you can build and rebuild where you're doomed to suffer nature's depredations.

We're all subject to nature in greater or lesser degrees, and certainly someone living 100 miles north of the Gulf can't be said to have put themselves knowingly at high risk of losing his home to a hurricane. But someone living in a below-sea-level bathtub with the sea lapping hungrilly close to flood stage at the best of times can't say the same thing. And don't talk to me about it being needed for "low income" people who can't afford other places - who's aiding the most harm, the person who advocates deliberately placing them in harm's way knowing they're likely to suffer the most of any citizens, or the person who says, this is it, they must live where both they and their assets are safer? It is a hard calculus to decide it is better to move your philosophy forward by fighting for poor people to live in danger than fighting to find them safe haven.

Say no to Louisiana's political machine. Say no to those who want to live in dangerous places at the nation's expense. Say no to rebuilding those parts of New Orleans most at risk of future flooding, no matter how much history attends their storm-exposed bones.

September 20, 2005

I am NOT a diva (and if you say I am, I'll ruin you)

Oprah Winfrey, in non-diva mode.

Life, she is full of an irony all her own. Who needs comedy writers?

September 13, 2005

Death runs down a 16-year-old

I've never understood drunk driving. I know some people are addicted, but they've made a series of choices that led them to that place, and they are aided and abetted by a society that thinks, in its heart, "there but for the grace of God go I". Social shunning is as effective today as ever it was in the time before Christ, in the Middle Ages, in the time of the Puritans. Witness the campaigns against smoking - it is primarily predicated on social shunning. Those who cry, "health risks!!" are accurate - there are measurable and horrific health risks to smokers - but the bottom line enforcement mechanism is social shunning for committing an immoral act. That level of shunning and social disapprobation has never kicked in against drunkenness - in fact, drunkenness in certain contexts is seen as a rite of passage in the young, and a sign of youthful exuberance in the old. It is forgivable, even affectionately laughable, until it results in failed marriages, destroyed lives, and, thousands of times a year just in the US, murder.

Yes, it's morally reprehensible to light up even once, but it's sophisticated and adult, lively and exciting, to tip a few back, whether you're tipping beer, champagne, wine or whiskey. And yet I've never known second-hand smoke from a habitual smoker to fell a 16-year-old, leaving him dead beside the road. And I've never known smoking to end the lives of a Jeep-load of college athletes, or send their killer to jail for over a decade.

My own problems with drinking - and smoking, for that matter - have their foundation in Bible teachings, which condemn drunkenness. I've never quite been able to get over that last hurdle to saying that all drinking is wrong - a glass of wine with a meal, an occasional drink of something else alcoholic when you're going to stop after one and stay put for a while after, those things seem no more mind altering than a couple of cups of coffee or, for that matter, a sugar high. But it does seem ill-advised for most people, because I don't know anyone I've discussed it with who drinks who hasn't admitted to being drunk at least once. And who intends, when taking that first drink, to get completely blasted and wipe out the life of someone else? I doubt many of the ones who do exactly that. Maybe a little more social pressure against drinking would help.

The impetus for this latest screed is a post from Stacy at Not a Desperate Housewife. Remember the college athletes in a Jeep I mentioned above? One of them, Cody, was her nephew. And this week she's blogging about him as we move toward the fourth anniversary of his murder, on Sept. 16. She's not as hard line as me on drinking at all, but she understands no more than I do how anyone can get behind the wheel after doing so. I recommend you spend a little time at her place this week, and get to know Cody. It's okay if you cry.

When I was a journalist, back in the 1980s, my editor and I wrote a series of articles on drinking and driving. One of my assignments was to talk to the family of a young man from Kentucky who was killed by a drunk driver while doing nothing more exotic and provocative than walking along a road heading home from McDonald's with his friends in the dark hours just past midnight. It wasn't the first time that family had been touched - slammed - by a drunk driver. I've pasted the article in the MORE section. Read it and then tell me drunk driving - done by anyone, including your favorite people in the world - doesn't deserve every ounce of your disgust, disdain and denunciation. Then do what you can to make sure it never happens again.

[Link to NADH via MerryMadMonk, during one of his occasional emergences from the swamp.]

A victim:

âIâm sorry, sir â your son is dead,â he said

by Susanna L. Cornett

(Special section on DUI, The Oldham Era, LaGrange, KY, October 23, 1986)

It was a warm Florida evening, 1:30 a.m. on Friday, Aug. 9, 1985. Marty Pawlicki, a slender young man with dark blonde hair and smiling blue eyes, was walking beside a roadway with three friends, returning to their familiesâ vacation condos from McDonaldâs a short distance away. The crunch of tires on gravel behind them drew their attention, and they turned as a car sped past.

Then one of the group noticed that Marty was missing.

They found his body lying in the road. He was 16.

Dan and Dawn Pawlicki of Prospect were at the condo when a police officer came to tell them their son had been in an accident. They feared the worst, but felt heartened that the police officer hadnât immediately confirmed their fears. They went with him to the police station, where a sergeant drew Dan aside.

âIâm sorry, sir â your son is dead,â the sergeant said.

Dawn knew Marty had died when she heard Dan cry out. They told their three daughters when they returned to the condo.

âThe kids were crying out, âNo, no, not my brother!ââ David said, eyes red with tears as he recalled that night.

The driver that hit Marty was chased down by two witnesses to the accident. He stopped nearly a mile from the scene, the right side of his windshield smashed in. At his trial, he said he thought a kid had thrown a pop bottle at it.

He was arrested and taken to a hospital, where they found that he had a blood alcohol content of .16. He was charged with DUI, leaving the scene of an accident and manslaughter by negligence. Seven months later he was convicted of a lesser charge, vehicular homicide, and sentenced to one and a half years in prison. He lost his license permanently, and was given three years probation.

He was also ordered to pay all funeral costs.

Within three months of sentencing he was placed in a halfway house on work release; his job is at the same restaurant/bar where he was the night of the accident. He may be released on probation in February.

The Pawlickis donât think thatâs enough.

âI canât handle it, knowing heâs free and my son is still dead,â Dawn said. âIf he had been convicted of all the charges, he would have gotten 15 years.â

Dan thinks the laws need to be stricter, and that âwe need stronger prosecuting attorneys, stronger judges. I donât think half of them have backbone. And we need to bring up (the driverâs) past record.â

In the case of Martyâs killer, his past record was not allowed in court. It would have been telling: speeding tickets, reckless driving tickets, and two previous DUI arrests. In Kentucky, the DUI law states that if a person is deemed too intoxicated to drive, he must be arrested for DUI by the officer who stopped his vehicle. Also, previous arrest records are generally admitted in court during the penalty phase, after a conviction has been recorded.

Martyâs death was the second time a drunken driver had touched the Pawlickisâ lives. In October 1984, 10 months earlier, their eldest daughter Donna was walking across a Bowling Green street on her way to a party. She was a freshman at Western Kentucky University. A drunk driver traveling 50 miles per hour in the 35 mph zone hit her, tossing her 63 feet. She was in intensive care for three days, with a head laceration requiring 10 stitches. The only reminder of it now is occasional headaches.

Marty was very angry when the accident to his sister happened, Dawn said. He joined Students Against Driving Drunk (SADD) at Ballard High School, where he was a sophomore. His sister Jill, now 14 and a freshman at Ballard, recently joined the same organization.

The Pawlickisâ home in Green Springs subdivision near Prospect is on a quiet street of attractive middle class homes. Their lawn is manicured, their living room done tastefully in beiges and their mantelpiece a place for a photograph of Marty, taken at his 16th birthday party in July 1985. Behind the photo is a poem, hand copied by Donna from a book she found. In part it reads:

Even though the memories we have are beautiful,

And thinking back on them fills my heart with joy,

My eyes also swell with tears

Because we are so far apart

And I miss you very much.

###

September 11, 2005

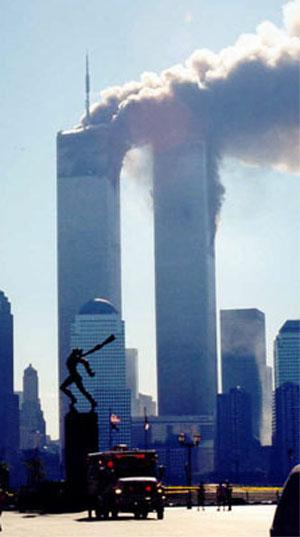

Remembering The Lost

[I posted this originally on September 11, 2002.]

Inside yet outside

On Tuesday morning, September 11, I heard on the Curtis & Kuby radio show that a plane had hit the World Trade Center. They thought, and thus I thought, that some small aircraft had veered out of its flight path. Not much reason for serious concern. I dropped off my laundry, called my mom on the cell phone, and watched the towers burn as I drove to work, almost literally in the shadow of the twin behemoths. I didn't hear until I reached Five Corners in Jersey City that a second plane had hit as well.

At that moment, no one had mentioned terrorism.

The Twin Towers were New York City to me. From the first time I went to Manhattan in 1989, the WTC was my staging ground for jaunts into the city. I can see now, in my mind's eye, the PATH platform and the lower level with its newspaper stands and stop-for-a-drink-on-your-way-home bars. The first bank of escalators from the lower level was short, and advertisements lined the long landing to the next bank up. These were the longest escalators I've seen to this day, bringing people to the main shopping floor of the mall under the Towers - there was the Godiva store where I bought chocolate strawberries for my friend Desiree; the Borders where I got my ex-boyfriend a book on Renaissance architecture; and Ecce Panis, a most excellent bread store. I've always wondered â did the people behind those counters get out alive? I think it's likely. But so many, so many did not.

The last time I was through the WTC was 10 days before 9/11, when I was on my way to Willner's Pharmacy for homeopathic remedies. I remember it clearly because I took notes that day. There was a young man on the train dressed in a black t-shirt, black jeans ripped off just below the knee, black and white horizontal striped tights and army boots, his long sandy hair in braids brushed with red dye as if they'd rusted. He seemed so angry. I described him to myself, even drew a sketch. We both left the WTC center on the Broadway side.

I wonder if he's dead, or if he lost someone close to him. I wonder if he's angry about something else, now, or if real life could intrude on his self-absorption.

I work in Jersey City, and often drive on Montgomery Street. As you head east down the hill from Bergen Avenue, the Manhattan skyline is spread before you, so close you feel you could touch it. This time last year, the WTC dominated that view. Smoke dominated it for days after 9/11. Now, nothing dominates it. Somehow, that nothingness is the most intrusive of all. I want to say, every day: The WTC is still gone. Just so you know.

I sat with coworkers in the police director's office that day and watched the Towers come down, less than two miles away. But we saw it on television. One thing I regret is that I did not leave work to go help. I know they had hundreds of people helping at the waterfront. I stayed and answered the telephone. I did ask if they needed me. They said no. So I went home, and stood three blocks from my apartment and watched the smoke rise from seven miles away.

My friend watched it burn from the street below â the first plane hit just before she exited the subway many floors below. She left the building to find a world gone crazy, debris falling, people running. She hid behind something â a fruit stand? â and saw the bodies falling. Living debris. But living only for 10 seconds. She didn't see them hit. She heard it though. She ran for her life.

Because I work for a police department, I know many people who went to Ground Zero that first day, who helped search for survivors. One officer told me that as he walked through an open place near the WTC site, another officer nudged him and pointed. Lying on the ground, by itself, was a human leg.

That's one person whose family got a piece back.

Another friend of mine grew up in Hoboken. She lost several friends in the WTC. One was identified from DNA. All they found was a piece of flesh, unidentifiable as to which part of the body it came from. I wonder if that person jumped, or was destroyed in the rumbling crash of the towers.

The aftermath of 9/11 was surreal for me. I didn't lose anyone I knew personally, so I felt on the fringes of the grief, and yet I felt so deeply what was lost. I didn't know how to grieve that way. I went to a memorial, finding myself at the end crying in a hug with a Port Authority police officer, a stranger, who had lost dozens of her comrades. I gave candles to a family who lost their daughter, so they could light them beneath her photo on the Wall of Remembrance. In early October, I went to Manhattan for the first time since I followed the angry young man from the subway. I walked south from the 9th Street PATH station, and watched the world change block by block â fewer regular people, more police, more and more flyers saying, I love him, I can't find her, please help me, with photographs of handsome young men and women. I cried at the memorial in front of the church, looking at the charred remains of the shopping mall â a singed sign reading âBordersâ still in the window. In November â Thanksgiving week â I went with a law enforcement friend to Ground Zero. Because she was an officer, we got a grand tour, driven throughout the site on a golf cart, by one of New York's Finest. I saw the office buildings with offices still intact, the outer wall gone, leaving them looking like a charred dollhouse. I saw the girders that landed in the shape of a cross, which workers left alone as long as they could. And I traced with my finger the etchings of sorrow in the soft wood railing of the viewing platform, left there by family and friends. One said:

Every day, still, I'm reminded of 9/11. I don't see the towers as I drive to work. I don't see them when I drive down Montgomery. I don't see them when I go to Liberty Park. When I ride the PATH train, there seem to be fewer people, and I wonder â how many of those that I pressed up against as we rode this modern cattle car, before 9/11, ended up a strip of flesh as a result of terrorists who hate us? Often, I ask a friend at church how her cousin is â the cousin whose firefighter husband didn't come home that day. The answer has gotten more positive in the past few months, but I think it will be years before the shadow is gone. I don't have to work at remembering â it's there, all around me, every day.

It's hard to convey to people who aren't here just how much 9/11 runs as a thread through everything now. It's not a pervasive sadness that keeps me from enjoying life. It's not a consuming anger that drains my energies. It certainly isn't a mawkish sentimentality fed by a ratings-hungry media. It reveals itself, I suppose, as a realization that yes, it can happen here. And as a determination to see that it doesn't happen again. I can't bring back the innocent people with good lives ahead of them who instead died in the most abject terror and hopelessness, because of the hatred and megalomania of an arrogant and heartless few. I can allow their deaths to sink into my heart, and grow into a resolve that says, Never again.

Never again.

Susanna Cornett

September 11, 2002

September 06, 2005

I...Can't...........Resist.......!!!!!

I do try, I really do. But I'm just ... overcome...

I haven't been blogging lately, but I probably should. I certainly have sufficient rants. Lately I've written to two media types ranting about their work, even though I probably should have kept my mouth shut. In the first instance for sure, since I got a bit more personal than I should have.

And that's the problem. When I review what I've written over the last few years, some of it I really like and I'm very proud of. Some of the rest of it I'm not proud of, and some I'm quite ashamed of. I've always thought of myself as laid back and not inclined to temper, but in recent years I've had to accept that that view is self-delusion. What I do is hold it in and hold it in and hold it in and then spew, often saying more than I meant to or speaking more harshly than I ought. One reason I've not written here in a while is that I'm struggling with a desire to be more measured thwarted by a tendency to fly off. While the rants may be interesting to read sometimes, they're not fun to look back on, especially when my imprudence remains bright and shiny right online for everyone to access in perpetuity.

I will say, though, that this morning my exchange with the media person who got to me was fairly measured and, while strong, not mean-spirited. I may or may not post it, I haven't decided. But just know that one reason you don't see much of me these days is because I'm struggling with a desire to have my writings be more reflective of my philosophy of life and fair play rather than glimpses of my uncontrolled annoyances. It's difficult because it's annoyance that usually spurs me to write.

I'll come to some middle ground, I promise :).